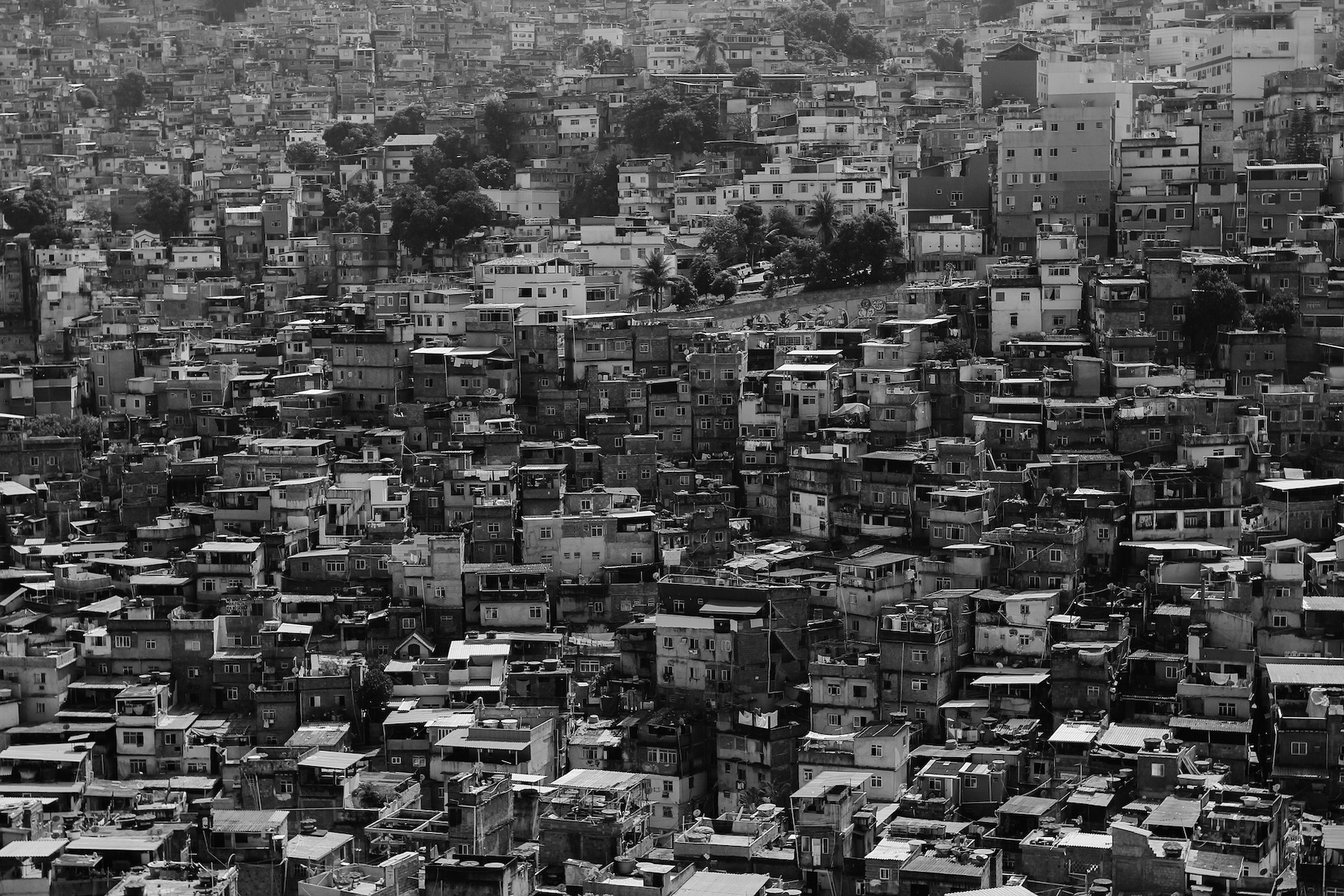

There are many scientific projections from research centers referenced around the world on the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil in the coming months. In none of them, however, is there a deep analysis of the reality of the favelas, which is radically different from the other urban territories because it does not fully count on the fundamental services for caring of life. Ignored by researchers, by the population, and also by governments, the favela continues to be seen mostly from the dangers it is supposed to offer. If before it was a territory of criminality, today, in the midst of the pandemic, it is the place where the disease can spread uncontrollably.

According to Regina Bienenstein, professor at the Graduate Program in Architecture and Urbanism at UFF and co-author, together with Glauco Bienenstein and Daniel Sousa, of one of the chapters of the recently released book The Coronavirus and the Cities in Brazil: Reflections during the Pandemic, organized by architects Andrea Borges and Leila Marques, the favela is an expression of how low-income workers are treated in our cities. This reality has its origin in the country’s industrialization process, which took place, explains the professor, “in a context of insufficient wages for the reproduction of the workforce, which do not include spending on adequate housing. In addition, land and housing, in capitalist cities like ours, are commodities. Thus, only those with sufficient resources to buy them in the private market have access to them. With no income and no response from the State, the occupation of some empty land unfit for housing, and ignored by the real estate market, becomes the only way.”

The researcher, who also coordinates the Núcleo de Estudos e Projetos Habitacionais e Urbanos (Center for Housing and Urban Studies and Projects – NEPHU), where she carries out outreach activities to provide technical assistance to the popular movement in its struggle for the right to housing and the city, highlights that this occupation process never occurred without setbacks. The “tolerance” pact of the public authorities and real estate capital in relation to this type of housing was threatened whenever land became of interest to the real estate market, accompanied by removal proposals, including through public policies. “In the 1960s, such a proposal proliferated in Rio de Janeiro and, more recently, it returned to the agenda during the period of mega-events, such as the Olympics. Many families were removed from the new axis of the advancement of real estate capital in the city,” she points out.

The researcher, who also coordinates the Núcleo de Estudos e Projetos Habitacionais e Urbanos (Center for Housing and Urban Studies and Projects – NEPHU), where she carries out outreach activities to provide technical assistance to the popular movement in its struggle for the right to housing and the city, highlights that this occupation process never occurred without setbacks. The “tolerance” pact of the public authorities and real estate capital in relation to this type of housing was threatened whenever land became of interest to the real estate market, accompanied by removal proposals, including through public policies. “In the 1960s, such a proposal proliferated in Rio de Janeiro and, more recently, it returned to the agenda during the period of mega-events, such as the Olympics. Many families were removed from the new axis of the advancement of real estate capital in the city,” she points out.

Brazilian cities have already been born, as Regina notes, with this brand, which demarcates spaces and bodies, and produces forms of exclusion on many and deep levels. According to her, “her mode of management and production resulted in a pattern of urbanization that is expressed socially and spatially in two types of articulated and unequal territories: one provided with the most modern in terms of services and infrastructure, where the sectors with higher incomes of our society and another, the popular city, devoid of all the elements that signify the bonus that urban life can offer.”

This large territory “on the margins”, where a significant portion of the population resides and which is “precarious, dense, unhealthy, subject to different types of risk and where there is often no water supply, sewage network and regular collection of waste,” is a fertile environment for the contamination of a variety of diseases. And it would be no different with COVID-19. In these territories, as it is possible to follow very explicitly in the last month in Brazil, public actions have been restricted to the recommendations of basic care, such as making social isolation, keeping homes ventilated, and hand washing regularly. But are these actions possible, given the particularities of these spaces?

“The question that remains is: how to be quarantined if people living in favelas rarely have formal work, if the rate of self-employment is high and unformal jobs are the only way out to survive? How to ventilate the houses? We are talking about houses that are often congested, with small and insufficient windows for good ventilation. How to wash your hands in houses where the supply of drinking water is intermittent and even non-existent?,” stresses Regina.

In practice, for the favela residents, “it is a catch-22”. The daily struggle for survival is part of its reality, with or without a pandemic. “This struggle is mostly done through informal activities on street corners and in the streets of our cities. Being prevented from exercising them has the immediate consequence of hunger. In addition, there are unhealthy conditions and lack of sanitation and insecurity in land ownership.” The architect points out that currently, in the state of Rio de Janeiro, evictions and forced evictions continues to occur. “This happens despite the fact that the Public Defender’s Office of the State of Rio de Janeiro has filed actions to suspend such initiatives until the critical phase of the pandemic has passed. Such conditions make the scenario experienced by this population extremely complex,” she denounces.

The struggle has also translated into ways of obtaining emergency aid that governments have been willing to offer in the context of the pandemic. Favela residents have faced, for example, the painful bureaucratic demands of emergency aid to have access to a minimum of resources that, as Regina recalls, do not even reach what is currently considered a “minimum wage”. In this context, emphasizes the teacher, “it is difficult, if not impossible, to stay at home. It is a painful and cruel choice!”

As if all these adverse situations were not enough, “there are still those who, inside their cars, that is, protected from COVID-19, march out demanding workers to return to work who will also have to face daily trips on public transport without the protection measures,” denounces the NEPHU coordinator. And once contaminated, what remains for this population is to face the emptying of public health, both in terms of hospitals, as well as equipment, infrastructure, and human resources adequately remunerated at Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS). “COVID-19 highlighted and enhanced the health crisis. The middle class, if they become infected, can afford health insurance and guarantee a place in a hospital, but the poor, who live in the favelas, will hardly have access to what they need,” she emphasizes.

To cope with this bleak scenario, with an almost complete lack of resources, part of the population living in the favelas has been articulating themselves to protect themselves and try to meet the basic needs of residents in an emergency situation. According to Regina, “in the construction of the defense of these territories, the creation of support networks is essential, since the support of the public power is clearly below the expressed needs, especially for the informal population that has no registration or registration on official platforms. And NEPHU, in partnership with the Office of Outreach Affairs at UFF, has been doing important work in this scenario.”

Palloma Valle Menezes, professor at the UFF Department of Social Sciences and member of the Marielle Franco Favela Dictionary, a virtual and public platform for the collection and production of knowledge about favelas, also reports a large number of collective initiatives to combat COVID-19 from those territories. The Dictionary, developed by a group of favela residents and researchers, in a partnership idealized by Sonia Fleury (from Fiocruz) and which includes representatives from Morro Santa Marta, Cidade de Deus, and Complexo do Alemão, articulates a production network of knowledge inside and outside academic spaces.

Coordinating the entries production in the Dictionary, Palloma informs that requests for the dissemination of initiatives to combat coronavirus have recently started to arrive in these territories. In view of this, according to the teacher, “all efforts to focus on a broad mapping of forms of aid to favelas began to be focused. News about coronavirus was mapped in these territories, materials about the disease that were being produced by and for favelas, as well as reports on what local residents and collectives are thinking about the subject. More recently, calls for tenders and funds have emerged to support groups active in the fight against COVID-19,” she highlights.

As an example, Palloma emphasizes the mobilization generated in different communities from preventive disinfection actions against the spread of the new coronavirus carried out in a favela in Niterói, in Central do Brasil train station, in ferries, in the subway, and in areas with greater circulation of people in the city of Rio de Janeiro. “Residents of Morro Santa Marta started to advocate that this sanitation process be carried out in all favelas. But they knew that if they were to wait for the government to do so, it could be too late. As they are fully aware that the fight against COVID-19 is urgent, they had the idea of carrying out the process of sanitizing the favela by themselves. They obtained donations and have already organized volunteers to start the process, with the appropriate safety equipment.” There are many initiatives and can be followed by accessing the Dictionary.

Even with so many efforts coming together, the precarious conditions of the favelas sometimes prevent collectives from being successful in their initiatives. Palloma emphasizes that, in the favelas, more and more residents have mourned the death of neighbors, relatives, and friends. “The reports posted by them on social networks show how we are not only dealing with numbers but the stories of real people who, unfortunately, are not being treated properly.”

Faced with increasing and frightening numbers, which hide the stories and lives of real people, in the context of the favelas, the responsibility for social isolation becomes increasingly urgent, reinforce the researchers. Committed to her object of study, far beyond books, Regina Bienenstein points out the urgency of staying at home at that moment, as well as the need for the participation of the whole society in support networks, with emergency actions, and practical measures demanded by favelas residents and other popular territories. In addition, she highlights, “it is necessary to reinvent an urban policy that articulates mobility, sanitation, housing, land usage, and occupation, in order to privilege the construction of a democratic and fair city, in place of the paradigm adopted recently and turned to the city as a commodity. It is clear that, in this (re)construction, the public university, free, with quality and socially referenced, will play an important role, making its knowledge available to society and reinforcing works that today are developed side by side with the population.”

Photo credits: Pixabay