In the middle of the 21st century, talking about drugs in Brazil is still taboo, although the number of deaths resulting from government policies to combat them multiplies year after year. According to data from the Brazilian Observatory on Drug Information, for example, between 2000 and 2015, there was a 60% increase in the number of deaths caused directly by the use of narcotics in the country. And it doesn’t stop there: the damage resulting from its stigmatization is countless, preventing the free flow of information on the subject, in the most different areas of society.

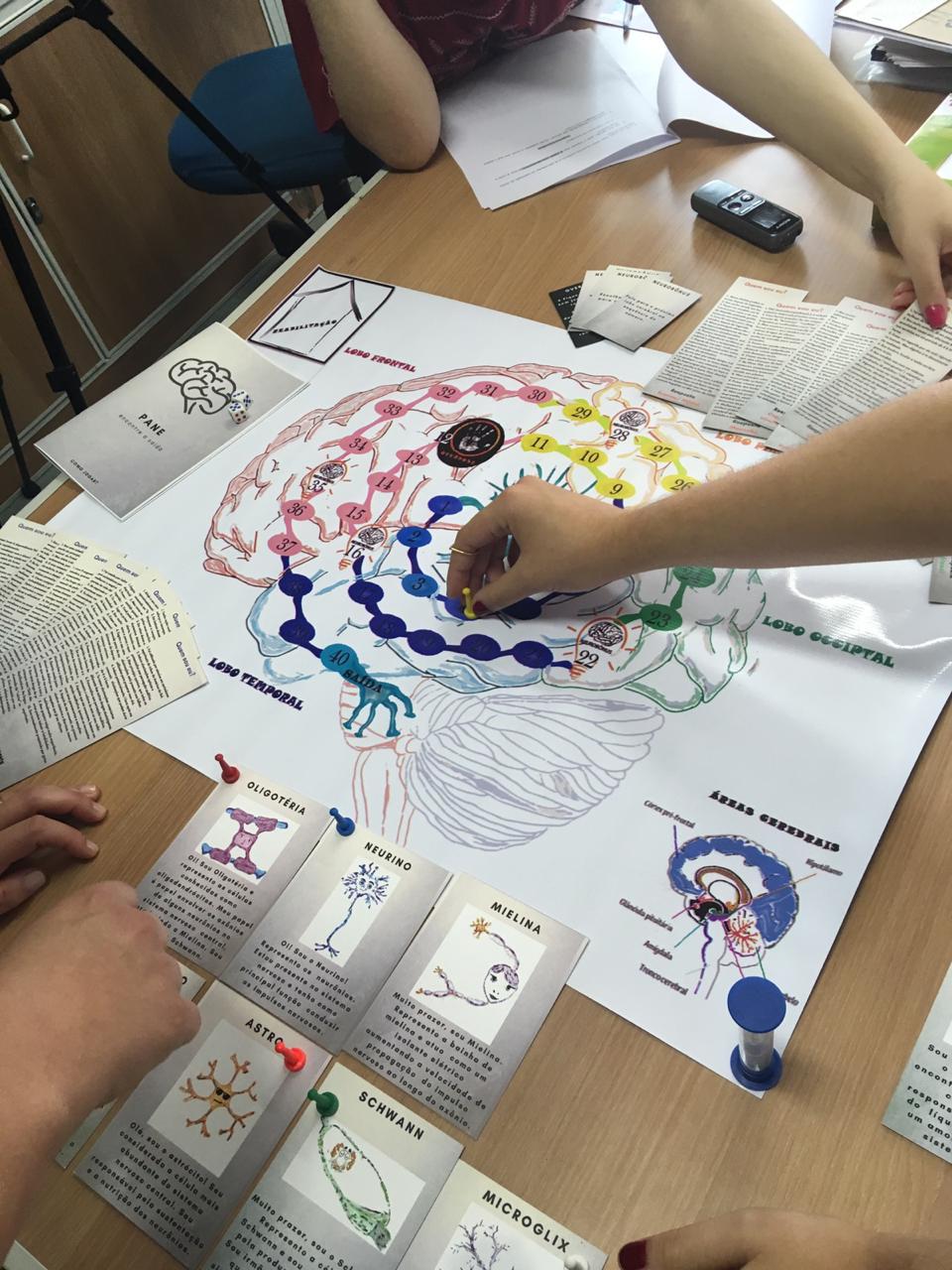

Against this trend, a UFF project takes a preventive approach to schools to address the issue, using an innovative methodology. By associating neuroscience with gamification, students and collaborators from the Núcleo de Pesquisa, Ensino e Divulgação e Extensão em Neurociências (Center for Research, Teaching, Dissemination, and Outreach in Neurosciences — NuPEDEN) has aroused interest in the subject by children and teachers in elementary education. But not just them! Last year, the project received the UFF Award for Excellence in Innovation for Social Development: Teaching Methodology in Combating Drug Use. According to Priscilla Bomfim, coordinator of the work, the objective is, through “an analog, educational and collaborative game about drug abuse, licit or not, to stimulate reflection on the theme,” she explains.

As it is a collaborative game, as they evolve on the board, they have the perception of how important it is to work together and to exercise empathy, since they have the possibility, strategically, to help other groups in the evolution of the game.

Priscilla Bomfim

There are plenty of good reasons to bring this discussion to the school environment. According to UNESCO data from 2017, drug abuse strongly impacts education as it reduces school performance, increases dropout rates, and causes most students not to complete their studies and not even attend a university, contributing negatively to social development. To face this, UNESCO recommends, even, an approach in schools that favors “interactive teaching methods carried out by educators.”

Gamification, explains Priscilla, presents itself as a great tool for this, because “by nature, children like to play. While they play, we, teachers and researchers, are involved in the application of game tactics, within a specific narrative, in order to achieve an objective that is to learn.”

The visits of the NuPEDEN team to public schools in Niterói have been taking place since the second semester of 2018 and the receptivity of the school community seems greater at each meeting. According to the coordinator, this device has “a role in building students’ knowledge, as they are fully engaged during the session, often asking our team to return to play again,” she says. In each school, Priscilla explains, the dynamics with students are different. The duration, in theory, is 50 minutes, but often the time is extended due to the curiosity that the game arouses.

Organized in groups of up to six participants, each representing a cell or brain structure, in a board game, an environment is created that favors the emergence of questions and discussions around the theme. According to the researcher, “they feel very comfortable asking questions as the game develops, asking questions about neuroscience, actions in the areas of the brain, drug abuse, addiction, overdose potential, ‘bad trips’ and organ involvement.” The results, she adds, are very positive and encouraging: “students reflect critically on science, they manage to develop the task of working as a team and also their self-esteem,” she emphasizes.

Organized in groups of up to six participants, each representing a cell or brain structure, in a board game, an environment is created that favors the emergence of questions and discussions around the theme. According to the researcher, “they feel very comfortable asking questions as the game develops, asking questions about neuroscience, actions in the areas of the brain, drug abuse, addiction, overdose potential, ‘bad trips’ and organ involvement.” The results, she adds, are very positive and encouraging: “students reflect critically on science, they manage to develop the task of working as a team and also their self-esteem,” she emphasizes.

Throughout 2020, in the midst of the pandemic, the project remained active. According to Priscilla, “in order to maintain contact, even if it was virtual with our target audience, we continue to work on social media with the column #TáLigado? in which we present the drugs and their physiological effects, whether they are legal or illegal. We also publish articles and we are still preparing an electronic magazine that can be consulted online or in PDF and will be distributed free of charge in schools in the city and in the state,” he celebrates.

Priscilla collects remarkable moments of the work done with the schools during this first year of the project. One occurred during a game presentation at a school in Santa Rosa, a neighborhood in Niterói. A high school student, at the time, thanked the team for participating, saying that her dream was to become a nurse at Universidade Federal Fluminense: “she said that, after our visit, she was sure that this would be a reality. She said she would study hard and then create a prevention program against the use of legal and illegal substances in her community. The girl stated that she had never imagined how the drugs acted in the brain and how they could be harmful to the organism,” she recalls.

One of the project’s scientific initiation fellows, Thaís Magalhães, also experienced many moments of learning shared with the students: “the visits I made to the public schools in Niterói marked me a lot for observing the communicative power of the game, I mean, the power that the game itself has to channel information to them, who, at the end of the sessions, turned to us from NuPEDEN to ask questions, interested in knowing more about a specific drug and its effects. As if that were not enough, we observed that the game has a communicator potential to beyond the students, being able to reach parents, siblings, grandparents, friends, chemical addicts, which is impressive,” she points out.

The coordinator highlights yet another aspect of the game that, according to her, makes its action so mobilizing among students: “since it is a collaborative game, as they evolve on the board, they have a perception of how important is the collaborative work and the exercise of empathy, since they have the possibility, strategically, to help other groups in the evolution of the game, using ‘neurobônus’ cards, which work in this ability to put themselves in the other’s place.”

Thaís even recalls how much, during the presentation of the game at a national congress on the science of education, its cooperative aspect jumped out to the public: “everyone was fascinated by the idea of the game being collaborative and not competitive, like most of the games are, agreeing that this measure would help to promote greater integration between the participants and the development of the feeling of empathy,” concludes the UFF student.